"I can't tell you if the use of force in Iraq today will last five days, five weeks or five months, but it won't last any longer than that."--Donald Rumsfeld in 2002

So we're done now right?

On March 20th, 2003, the American and British armies surged across the border into Iraq, hoping to overthrow the rule of Saddam Hussein and destroy his alleged stockpile of dangerous weapons. The final decision to go to war involved a combination of factors at the highest levels of the Bush administration, most of which have been detailed in part one this series. When the invasion commenced, nearly every senior administration official was convinced that Hussein's army would break quickly, that the Americans would be welcomed as liberators, and that power would transfer quickly and easily from the the victorious American forces to an Iraqi governing body. Looking back, these assertions seem incredibly short-sighted. In part two of this series on the making of modern Iraq, we take a good look at the critical mistakes the American administration made during the first few months after the invasion. Ultimately, these mistakes directly contributed to the creation of a powerful insurgency within the country.

Yup, we're done here. Good work team!

President Bush and his main advisers were half-right about Iraq. By May 1st, the Iraqi army had been completely defeated (at least in a conventional military sense) and many Iraqis (but certainly not all) were optimistic for the future. However, the mood quickly soured between the Americans and Iraqis as the presence of foreign forces endured long after Baghdad had fallen. Perhaps the single greatest factor which contributed to the problems the United States would face in Iraq was the lack of strategic planning for the future of Iraq once the U.S. claimed victory. The military's command structure was plagued by disorganization and the lack of a coherent strategy. The war planning process had placed all of its attention on winning the war, with little concern for securing the peace afterwards. All of this meant that instead of quickly building up a governing coalition by securing the trust and cooperation of prominent tribal leaders, the military's lack of strong direction allowed regime supporters and opportunistic rebels to build up their own forces. But this aimless policy alone wasn't necessarily enough to create a vicious insurgency. For that, it would take three very large mistakes in the American administration of post-invasion Iraq.

By mid-May, it was starting to become clear that the occupation of Iraq would take a little longer than a few short weeks. On May 9th, President Bush appointed former ambassador Paul Bremer to be the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority (basically the replacement government for Iraq until full elections could be held). On his first day in office, Bremer and the CPA purged the Iraqi government and administration of almost all members of the Ba'ath party (Hussein's political party and the only legal party in Iraq previously). Like the policy of de-Nazification before it (which tried to rid postwar Germany of all of its former Nazis), this policy banned the vast majority of the country's civil officials from participating in government or administrative services. At first, this seems like a great way to remove all traces of Hussein's influence in Iraq. But the problem with this policy (aside from being very indiscriminate regarding who it affects) is that in a single-party country like Iraq anyone who knows how to do anything is a Ba'ath party member! Suddenly, upwards of 100,000 of Iraq's most competent people were kicked out of their old jobs, leaving new and often inexperienced replacements to pick up the pieces. While there were certainly a large number of terrible people in these positions (who probably deserved a lot worse than just losing their jobs), their usefulness in keeping the country from falling apart far outweighs the need to seek vengeance on every member of Hussein's political party.

NOT the Ba'ath party

Bremer's next move would prove at least as important (if not more so) in starting the insurgency. A few days after expelling the Ba'ath party from Iraq, the CPA ordered the complete dissolution of the entire Iraqi military. Once again, this may seem like the obvious decision during a war, but it is important to remember that the army had essentially ceased combat operations already. Most soldiers had returned to their homes or military bases to await further instruction from the American forces. With the army disbanded, over 400,000 people (nearly all young men of combat age) were suddenly unemployed and humiliated. Previously, there had been several post-invasion proposals which included using the Iraqi army for critical tasks such as infrastructure reconstruction and security. Not only would this plan have freed up the American military to conduct other affairs, but the Iraqis also would have felt a personal stake in rebuilding their own country. Instead, these tasks were delegated to the overworked and understaffed American soldiers. To make matters worse, the military was one of the only unifying forces in Iraq which helped transcend ethnic and religious differences. These were the individuals who knew the country, understood its cultural nuances, and had personal connections to the powerful people of Iraq. Instead of utilizing this knowledge and these relationships, the CPA drove many of them right into the arms of insurgent forces waiting to capitalize on their disaffection.

Bush: You're Fired!

Finally, the last major mistake in the initial months following the invasion was the decision to create a free market economy in Iraq at the expense of the already existing institutions and factories. This caused some major industrial centers to close and further increased unemployment (especially among the middle class), destabilizing an already shaky Iraqi economy. The free market economy, much like democracy, usually takes a long history of experience before it can become truly viable in a country. This sort of change does not easily take hold overnight. In all of these decisions, the CPA proved short-sighted and idealistic in its handling of post-invasion Iraq. Rather than incrementally reform Iraq into a more stable and peaceful nation using its existing institutions, they chose to fundamentally change Iraqi society, with disastrous results.

From the very beginning of the conflict, the initial emphasis of the military was focused too heavily on finding Hussein and his alleged WMDs rather than the more pressing concern of nation building. To date, only a handful of chemical weapons (and no nuclear or biological weapons) have ever been found (and even these were developed long before Iraq abandoned its weapons program in the 1990s). The initial invasion force was just big enough to defeat the Iraqi army, but much too small to actually secure the country. In essence, we were fighting the battle we wanted to fight, not that one that was actually being fought. By the time the United States issued a clear and direct plan for the long-term stability of Iraq in late 2003, it was far too late. The insurgency had begun.

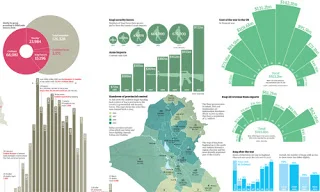

Division of Iraq by September 2003

In all, the difficulties of the first several years in Iraq were due in many ways to extremely poor strategic planning, several decisions which contradicted basic counterinsurgency models, and a mindset which ignored the growing insurgent problem for several months. Had the United States planned and executed a meaningful strategy of post-invasion stability, rebuilding, and power transfer, Iraq might have escaped the chaos and destruction of the following decade. This isn't to say that Iraq would be the shining example of a successful military overthrow by a foreign power, but it's possible the United States could have left Iraq in better shape than when it first arrived. Clearly, the troubles of the current Iraqi government demonstrate that this still isn't the case. On the final post in this series, we'll try to understand how the insurgency helped give rise to the region's greatest threat: ISIS.

Tl;DR: The United States had almost no plan in place for post-invasion Iraq once it achieved victory. Because of this, a series of bad decisions were made which created the perfect conditions for a long insurgency in Iraq.