"I hope - and indeed I believe - that this agreement will lead to greater mutual understanding and cooperation on the many serious security challenges in the Middle East."- Ban Ki Moon, United Nations Secretary General

Lead negotiators after finalizing the Iran nuclear agreement

Negotiations on Iran's nuclear development program have been going on for over a decade. This week, a critical milestone in those negotiations was reached as the United States (along with the United Kingdom, France, China, Russia, and Germany) and Iran formally agreed to the terms of a final deal limiting its development of nuclear technology. If you recall, President Obama agreed to let Congress review the deal prior to it going into effect. They can now issue a nonbinding (symbolic) rejection of the deal, but Obama can still override their decision if they do not have a 2/3rds majority. This makes it nearly certain that the deal will be implemented.

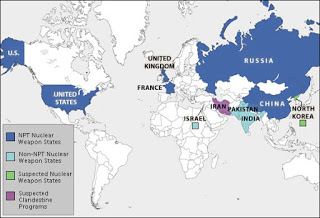

As we have discussed previously, Iran has been allegedly attempting to gain access to a nuclear weapon for several years (they have never outright admitted it, but they often conceal information about their program and enrich uranium to levels which suggest weapons development). Though more outlandish theories attribute this to a desire for regional military conquest or the destruction of the State of Israel, the main reason most nations seek nuclear weapons is for regime security and military defensive superiority. With these types of weapons, other states are highly unlikely to invade or launch military attacks against them.

Nations with nuclear weapons

To put it simply, Iran needs uranium to build a nuclear weapon. Uranium can also be used for energy and medical treatments, so it's not like uranium can be banned entirely in Iran. Uranium needs to be enriched (purified) from its raw form which comes out of rocks in the ground. Most medical and energy purposes only need uranium to be enriched to no more than 5% (100% being completely pure). Iran has agreed to seriously cutback on its enrichment of uranium and plutonium (both very rare and difficult to produce in quantities sufficient to make a weapon) in exchange for the removal of sanctions (trade restrictions on almost everything going into or out of Iran). The country will also have to allow inspectors into its facilities at any time to ensure they are keeping their end of the deal.

Worldwide uranium deposits

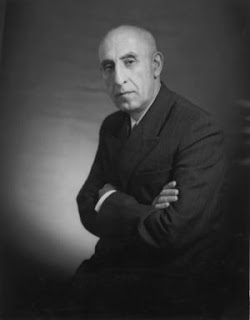

The deal has some wins for Iran (small amounts of continued enrichment for up to fifteen years, operation of some facilities, and the lifting of sanctions), and some wins for the U.S. and its partners (enrichment is limited to 3.7% and all facilities must give full access to inspectors). To ensure the continued cooperation of both sides, Iran still maintains some ability to enrich uranium and the U.S. can still reimpose sanctions if it feels like Iran is not living up to its end of the bargain. This balance helps keep both sides honest while the deal is in place. It is important to remember that Iran doesn't really consider America to be a shining example of honesty and integrity in international affairs (the CIA overthrew their elected prime minister a while ago). Iran distrusts America about as much as America distrusts Iran. Because of this, both sides need to feel they have some ability to re-escalate the situation if needed (otherwise no deal would ever be agreed to in the first place).

Former Prime Minister of Iran Mohammad Mossadegh

Many critics point to the continued enrichment of uranium or the maintenance of some facilities as signs of a terrible deal. To these opponents, any deal which does not entirely remove Iran's enrichment ability and nuclear research facilities is unacceptable. However, it is critical to point out that such a deal is equally unacceptable to the Iranians. They would never accept a deal like that because it amounts to complete capitulation to the American demands. (The real reason for most of the American, Israeli, and Arab Gulf opposition is because the lifting of sanctions will eventually strengthen and empower Iran.) Since the U.S. and its allies could theoretically reimpose sanctions at any time without serious repercussions, Iran would lose all of its bargaining power to have sanctions lifted again in the future if it removed all ability to push back using uranium enrichment. In short, agreements are about compromise, not capitulation.

Furthermore, if the complete removal of Iran's enrichment and research abilities is the only measure of a successful deal, then what other alternatives are there when such a deal inevitably fails? Short of imposing more sanctions (which is about as unlikely to work as continuing the sanctions has in ending the program), the only other option is military conflict. Their facilities can be bombed and damaged (but not entirely destroyed), but this will only delay their progress and likely embolden the regime to push even more aggressively for a nuclear weapon. In that scenario, the only means of truly ending the threat of a nuclear Iran is to remove the regime itself. This is an incredibly dangerous and destructive option (one which ought to have been learned through the experience in Iraq).

Centrifuge used to enrich (purify) uranium

Even if this deal breaks down and Iran begins racing to develop a bomb, the military option is always available in stopping this. As it currently stands, most estimates place Iran's "breakout time" (the time it would take Iran to have a working weapon if it decided to do so) at about three months (though Israel's own intelligence suggests it is much longer). Most estimates place the breakout time under this recent deal at least a year. With international inspectors and scientists constantly monitoring the nuclear sites, it is highly unlikely Iran could develop a weapon in secret (not to mention every American and European intelligence agency will be closely monitoring this newly available data). It would also be a large red flag if Iran suddenly expelled all of the inspectors and scientists, much like Saddam did in Iraq in 2002. Simply put, no other option presents the same reasonable promise of success as the current negotiated plan.

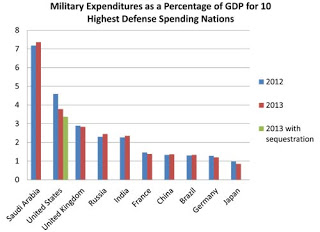

How will the region react to this? It all depends on the willingness of Iran to maintain its end of the deal. If Iran starts violating the terms of the agreement or starts acting shady about its program again, Saudi Arabia and other key players may begin planning for their own weapons program. Though Saudi Arabia already has the preliminary makings of a nuclear program, the country is highly unlikely to actually develop it unless the threat of a nuclear Iran is imminent. This is because the U.S. and its allies can put a lot more pressure on Saudi Arabia to stop a weapons program early in the process. This would likely be done by cutting military arms deals, ending the import of Gulf oil, and cutting diplomatic support to Saudi Arabia. Iran, often by its own actions towards the West, has already cut itself off from these options years ago.

Saudi Arabia spends a lot of its money on military hardware

Whether successful or not, this deal is an historic change in the now decades long dispute over Iran's nuclear program. What remains to be seen is whether both sides hold up their respective ends of the deal. Opening up Iran to more trade options and outside influence might allow it to one day conduct shady arms deals with regional militant groups, but it can also increase the Iranian people's connections with the outside world. When people are exposed to the ideas and interactions of the wider world, they tend to become less violent towards them. This isn't to say that Iran's leadership will suddenly become friends with America and other Western powers, but Iran's people will have more positive exposure to these influences. In the long term, this change in U.S.-Iranian relations can slowly help repair the damage done by decades of mistrust and subversion. In all, lasting peace can only be achieved by mutual understanding, not mutual destruction.

TL; DR: The only real alternative to an Iranian nuclear deal is armed military intervention. This deal helps prevent that.