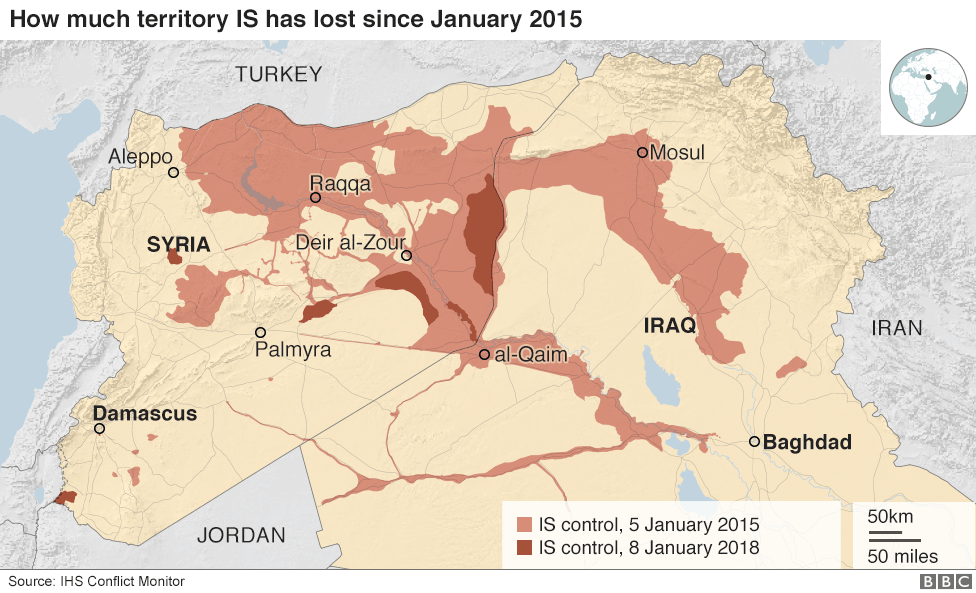

ISIS has lost even more territory since this map was created.

Last month, the president made an unexpected and controversial policy change via Twitter. Of course, this isn’t exactly a new phenomenon by now. But the president’s declaration that “ISIS has been defeated” immediately found itself to be the target of intense criticism and backlash. The subsequent decision by the president to rapidly remove military forces from Syria proved equally controversial, sparking condemnation from both parties. Even the president’s own intelligence agencies dispute the claim that the group is defeated, saying “ISIS is intent on resurging.” So it’s clear that some remnant of the group remains, but just how much? This week, we’ll examine the remaining threat that the “Islamic State in Iraq and Syria” (ISIS) poses to the region and the impacts of America’s impending withdrawal.

The group known as ISIS (or Islamic State to most of the rest of the world) gained infamy around 2014 when it began a massive military operation to seize substantial sections of Iraq and Syria. In the chaos of the Syrian civil war and the lingering problems of post-occupation Iraq, ISIS took over major cities including Mosul, Fallujah, and Raqqa. At its height, the organization controlled an area the size of Great Britain as part of its self-described Caliphate. Its fighting force had been estimated to be anywhere from 31,000 to 100,000 people. But years of intense fighting with Iraqi and Syrian military forces (as well as American air strikes) have depleted the territory of the group by nearly 99%. They have increasingly switched back to hit-and-run attacks against weak targets out of desperation.

Former Defense Secretary James Mattis, who resigned in part because of America’s withdrawal from Syria.

But this doesn’t mean that ISIS is truly defeated. Most estimates still place ISIS membership at around 30,000 people. To put this in perspective, when president Obama declared the end to military operations in Iraq back in December 2011, the extremists that formed ISIS numbered barely more than a thousand. Within a few short years, the absence of a powerful military force in Iraq allowed the group to slowly build its power base by seizing strategic areas, conscripting tribes into military service, and spreading its propaganda. There is a general consensus among policy and security analysts that another American withdrawal would open the door for ISIS to emerge yet again. To that point, ISIS continues to launch attacks against military personnel and civilians, such as the attack that killed four Americans just a few weeks ago.

There will certainly be regional impacts as well. One of the biggest supporters of the American presence in Syria and Iraq is the Kurdish forces. Many of these troops fought directly alongside American soldiers and share strategic intelligence about threats in the region. The American withdrawal will leave them isolated at a time when Turkey (which believes that the Kurds are separatist terrorists) is poised to strike. The American withdrawal substantially helps Turkey in their conflict with the Kurds, but it will also greatly benefits Iran and Russia. Iran has been flooding Syria with weapons and fighters to help in a proxy fight for Syrian president Assad (who shares a version of the Shi’a belief of Islam like Iran). Russia is also propping up Assad as one of the only friendly regimes to Russia in the region. The United States has previously been actively working against Iran and Russia, so it seems likely that the decision to withdrawal would surrender Syria to Russian interests. This, by extension, would be harmful to the interests of nations like Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Israel.

The leaders of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and America, who solidified their partnership by touching a glowing orb.

But why should you care about the political interests of a bunch of far away countries in the Middle East? There is certainly something to be said about the United States refocusing its military effort and extricating itself from costly wars with limited strategic benefit. And the direct impact to the average American’s life is probably very limited by either staying or leaving Syria. But perhaps the biggest potential impact is simply that of ISIS (or a similar group) re-emerging again once the United States leaves. As we have seen in recent years, the destructive rise of these groups can spread to other nations, creating more instability and refugee crises. Now it’s not necessarily true that we need to “fight them there so we don’t fight them here.” After all, most people previously affiliated with ISIS are finding it extremely difficult to return to their home countries. But a withdrawal that is too sudden could risk the need to once again pull American forces back into the fray (many of whom are our friends and family members).

Ultimately, the United States must find a balance between finishing the mission of reducing terrorism in the Middle East and preventing endless war. This is a discussion that ought to be held as a national conversation. It is traditionally the job of Congress to declare war (and by extension to declare peace). But this conversation is difficult to have when major military and policy decisions are executed via Twitter after a phone call with the Turkish president. Unexpected decisions always have unexpected consequences. Whether the American military stays or leaves in Syria, the decision must be considered, planned, and executed in an informed and deliberate way. Anything else is just reckless.