Cuba's Guantanamo Bay has long been a popular destination for suspected terrorists to spend long walks in the yard, catch some rays in solitary confinement, or enjoy the surf in a new take on "boarding." For the past seven years, the Obama administration has been looking for any possible way to close this prison which is now famous for its seemingly indefinite detentions and questionable interrogation techniques. More recently, the administration announced a new initiative to close the facility saying, "Guys, we really mean it this time." Prisons close and relocate all the time, so why is this particular place so difficult? This week, we will break down the four main reasons closing "gitmo" has been so difficult.

1) We don't know where to give them a trial

Anyone who has ever seen Law & Order (or any of the thousands of crime dramas on TV) can tell you that American criminal law is really complicated. American military law is equally complicated. But what happens when we can't even agree on whether we should apply criminal law or military law to a suspect? Well, you get the indefinitely detained mess of the Guantanamo Bay detainees. Like most things involving security and terrorism, this quagmire can be traced back to the aftermath of the 9-11 attacks. During the Bush administration, the primary emphasis was on capturing as many suspected individuals as possible and quickly extracting information from all "enemy combatants" (a legal term which has yet to be clearly defined) . Legal matters surrounding the rights of the accused or due process were abandoned in many cases in favor of preventing the next attack (at least that's what they believed).

Seems legit...

Obama's administration took a much more careful and calculated approach. From the very beginning, the plan was to treat all suspects as criminals and not "enemy combatants." In civilian courts, the burden of proof is much higher for conviction than military courts. The administration wanted to demonstrate the resilience of the American judicial system, so they insisted on using criminal trials. This worked a few times, but when 9-11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammad was set to be tried in downtown New York, the backlash was too hot to handle. But why was everyone so worried about KSM? Surely he would never be acquitted of his crimes, right? Well.....

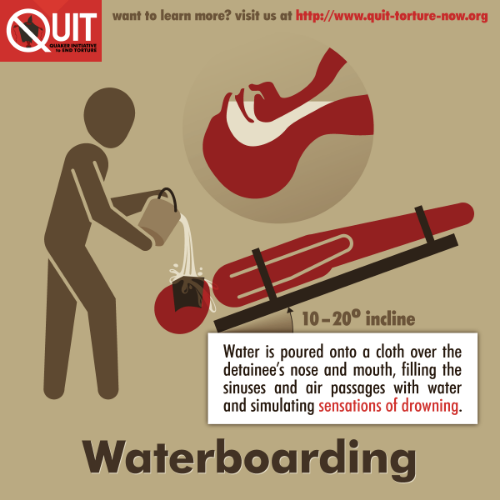

2) Enhanced interrogation Often makes testimony invalid

Stress positions, sleep deprivation, waterboarding...what do all of these have in common? They have been classified as inappropriate methods of enhanced interrogation. In a legal sense, this basically means that any testimony or conversations gained using these methods (of before Miranda rights have been given) cannot be used in a court of law. So even though KSM fully admitted to doing nearly all of the horrible things of which he has been accused, it probably can't be used against him since he wasn't explicitly told he has the right to shut the hell up. In criminal law, this makes sense. After all, the 5th amendment is a pretty nice protection to have.

Well, maybe not always nice...

There is still plenty of evidence against him (and the several other detainees who face similar legal obstacles). But without an airtight case, nobody wants to take the chance of putting them on trial, only to have them acquitted based on a legal technicality. Since double jeopardy is also a thing (except when it totally isn't!), nobody wants to be the one who let self-admitted terrorists get away.

The administration is still trying to find a way to compromise on the legal status of detainees (criminal, military prisoner, or some sort of hybrid status). For now, enhanced interrogation has largely been discontinued in favor of legal, humane methods of intelligence gathering which work much better anyway. Recent comments by presidential candidates like Donald Trump (whose hairpiece belongs in gitmo for crimes against humanity) about bringing back waterboarding (and doing "much worse") will only further complicate the issue. Aside from being morally questionable, these methods are also a bad idea because.......

3) Some of them are totally innocent...or at least they were

Granted, most of the truly innocent people have already been cleared and released to places like Oman and other Middle East nations. But determining the guilt or innocence of a particular suspect can be extremely difficult. On some occasions (especially during the war in Afghanistan), all it could take was a rival farmer telling U.S. troops "hey that guy works for the terrorists" for someone to land themselves in prison. To be fair, a lot of Taliban members were correctly pointed out and removed from the battlefield this way. But sometimes, your only crime was being mean to the other guy or having a nicer goat.

I went to jail for this?!?

Now why don't we just let all the clearly innocent ones go? After over a decade being treated like a terrorist, some people have started to take it the wrong way. Like in Europe, prisons are notorious for being breeding grounds of radicalism. After all, being stripped of all freedoms (except religious practice) tends to make people angry and desperate. So some who were innocent at first might be extremely motivated to seek revenge once they get out. And unless you are Tom Cruise, you can't imprison someone for a crime they haven't yet committed.

Tom Cruise, use your witchcraft to save us!

So if we can't give them all trials, and can't let them all go, couldn't we just move them somewhere less controversial? Nope, because even that is controversial.

4) Nobody wants them moved to the mainland

Simply moving detainees to another prison doesn't really do much to solve the problem the their legal status, but at least it removes Gitmo as a symbol of sketchy American legal practices. Even though these people would be housed in super-maximum security facilities and would probably spend their whole lives in solitary confinement, most Americans react very negatively to the idea of having suspected terrorists in their area.

Not in my backyard?

Instead, many of them have been moved to other countries for detainment and trial. The ones who remain now are the most difficult cases, whose final status has yet to be determined. Though it looks like Gitmo's days are numbered, the underlying problems which started this mess mostly remain. What's needed is a codified set of rules of engagement and detainment policies for those captured and suspected of terrorism outside the United States. On the one hand, suspected terrorists are clearly engaged in a type of warfare against the United States. On the other, indefinite detentions and loose conviction standards set a dangerous precedent for such a broad definition of people. Until this is finalized, Guantanamo Bay will likely remain as mired in controversy as its prisoners.